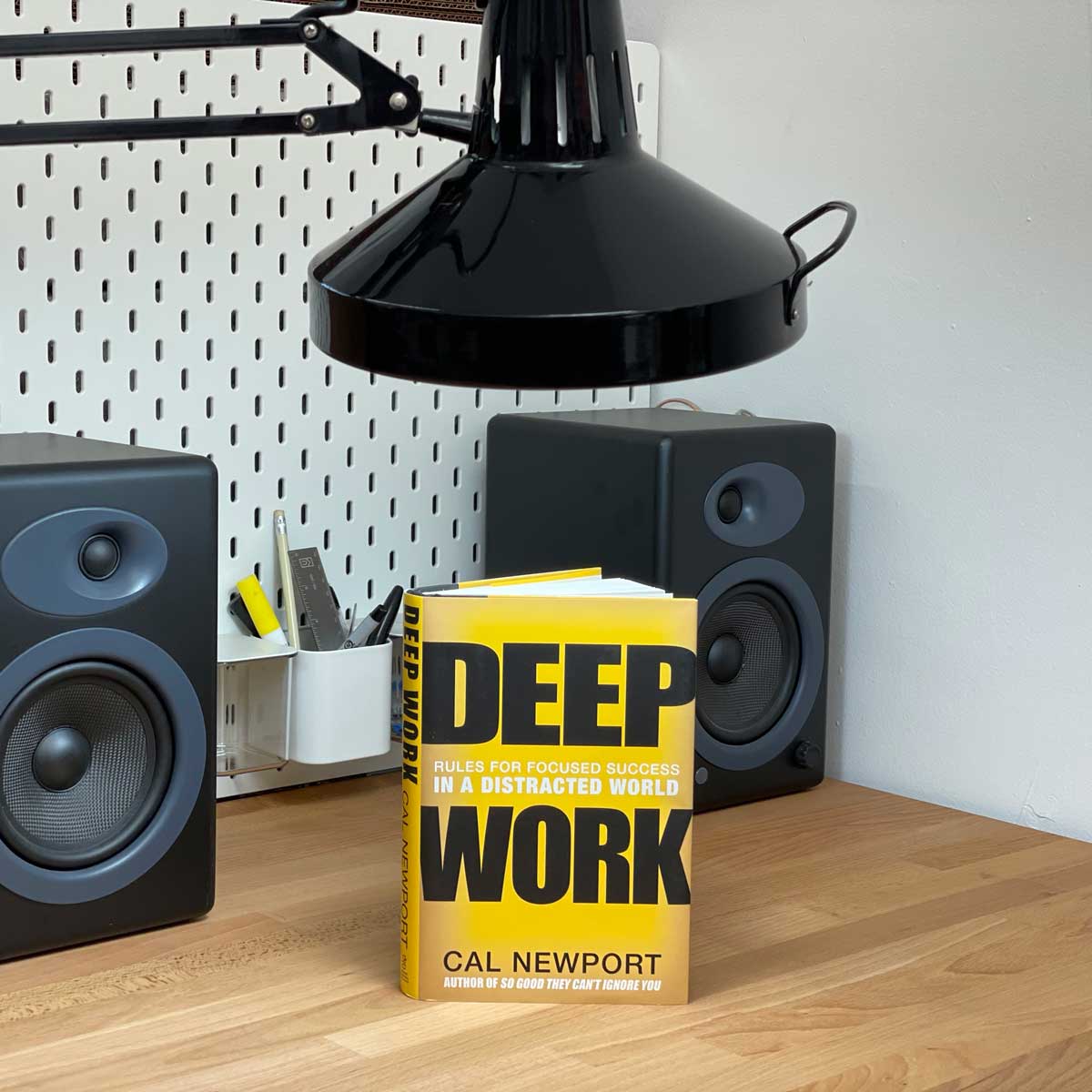

Has anyone ever recommended the book Deep Work to you? Or mentioned Cal Newport? It’s probably because it’s one of those books that crystalizes a lot of thoughts people already had into one cohesive work that contributes meaningfully to their lives. One of the things I really like about it is that it weaves a common thread from problem to solution to action in order to make it possible to incorporate the discoveries from modern psychology into your daily routines.

From architecting your environment to arranging your day, the results can truly be life changing. Yet, as with many dramatic shifts, they can be hard to stick to.

It actually had such an impact on me that it inspired me to start developing a timer to help with my productivity sessions.

But if you haven’t read the book yet, I hope to provide you with some value by summarizing some of his high level insights into things you can put into action. One of those actions could potentially be to read the book for yourself! If you’ve already read the book, perhaps this can serve as a refresher that helps you get back into the Deep Work mindset.

What is Deep Work?

When I’ve recommended Deep Work to some folks they say they’ve heard of the book but wondered if there was really much more to it other than the title. I’ll be the first one to say that there are some books which basically have one insight and it’s encapsulated by the title. For example, “The One Thing” pretty much says you should work on one thing and could have been a short article. Deep Work is sooooo much more than just saying you should stay focused while you work. First of all, Newport is an academic who paints a very convincing picture of how our brains work, variables which affect them, and how to overcome these challenges. As such, he starts with a hypothesis instead of a definition:

"The ability to perform deep work is becoming increasingly rare at exactly same time that it’s becoming increasingly valuable in our economy. As a consequence, the few who cultivate this skill and then make it the core of their working life will thrive.”

This sets the stage for what I think is one of the most interesting things about Deep Work which is that it challenges you to think about your role in the world as more than just being a more efficient machine. He asks you to step back and examine your profession and ask yourself if it’s going to be possible to automate… whether by you right now, by your company within a year, or by society within a decade. It brings the notion of the “gig economy” into sharper focus which he explores even more deeply (excuse the pun) in his follow up book So Good They Can’t Ignore You.

The gist of it is that the world is changing and the skills that are valued will change too. Specifically, he highlights two:

-

Quickly mastering hard things

-

Producing at an elite level

And the things that these two features have in common is that you need to have the skill, the practice, of Deep Work mastered and incorporated into your life to succeed at them. Which this foundation, you’ll be sort of operating in a different lane than everyone else. You may not answer email in a timely manner but you could finish a book that shares your ideas with the world instead.

He also identifies 3 specific “archetypes” of success and examples of each…

-

Highly Skilled Workers (i.e., Nate Silver’s ability to process and analyze complex information)

-

Superstars (i.e. David Heinemeier Hansson* applying his coding skills to create Ruby on Rails)

-

Owners (i.e., John Doerr and those who invest in new technologies)

*Will mention of DHH always require a footnote? Time will tell and I haven't really followed the drama around his story but since some readers have asked, these are the examples mentioned by Newport so fall in the category of "book notes".

What Psychological principles does Deep Work identify?

The whole first half of the book is dedicated to exploring how daily work and life fractures our attention and excellent examples of scientific research are provided to support his points. I don’t think it’s very useful to you if I summarize them here, as they really make more sense as illustrations of specific things he’s explaining as you go. But I’ll highlight just a couple of the most important things I took away...

Distraction goes much deeper than multi-tasking. I think most of us are familiar with the finding that multi-tasking is actually tasks switching at a micro level. We can’t perceive that our brain is going back and forth but it’s really just doing two things poorly. But some findings go way beyond that… like the fact that even having a phone that’s turned off in the same room makes you less productive than working in a separate room than your phone. Or how the architecture of a building can influence productivity.

Flow promotes a sense of happiness and wellbeing. As discovered and then popularized by his book Flow, Csikszentmihalyi showed that people are happiest when engaged in challenging and rewarding work- even more so than when relaxing. And other happiness research by Gallagher shows that "Who you are, what you think feel and do, What you love is the sum of what you focus on."

There are also a lot of really interesting examples from history about famous thinkers who traveled and put themselves in isolation to complete some of their most consequential work. I think back on my own experience with this before knowing about Deep Work per se when I had completed all of my coursework for my Master’s Degree but hadn’t yet completed my thesis. I already had a full-time job and close to two years went by. Finally I took a week off from work and completed the whole thing in the 9 day block… often working late into the night.

How can you improve your ability to perform Deep Work?

Many books in this category sort of leave it at the “distraction is bad” stage. But the whole second part of this book offers solutions. Many of them are nuanced and he outlines them as four rules:

4 rules...

Rule 1: Think Deeply

Well, duh- right? The key to this one is that he doesn’t spend time here saying that you should do it but rather focuses on how. He breaks things down into different “philosophies” or approaches you can pick from:

- Monastic Like a writer locking themself away for weeks or months)

- Bimodal (Alternating long blocks of time from a day to a few weeks in which you do exclusively deep work)

- Rhythmic (Where you take a routine and do it for consecutive days- also known as the Chain Method)

- Journalistic (An advanced practice where you shift instantly into work mode and sip small windows of time- named for the habit journalists have developed by working on a deadline.)

- Ritualizing (Creating environments and routines to support the practice. These cues can become repeatable and predictable.)

- Grand Gesture (Like renting a room in a 5 star hotel, going on an international trip and coming right back, or going to a lake cabin by yourself to write.)

- Collaborative (When you leverage the “whiteboard effect” of having someone else there… but he recommends combining this with solo time to process the insights.)

Side note: the Rhythmic method is how I initially built my business while I had a full-time job- by doing an hour of work each day before work and an hour once I got home. Now I use a variation of that where I do computer work in the morning in my home office and then design and prototyping at my studio in the afternoons. If this list doesn’t quite click for you, they’re explained really well in the book but this should give you an idea of the outline or a refresher if you’ve already read it.

One additional cool thing he goes into as part of rule number 1 is a concept from business he read about called the 4 Disciplines of Execution (4DX):

- Identify wildly important goals

- Act on the lead measures- things that happen during the action

- Keep a compelling scorecard

- Create a cadence of accountability

“Hours spent working deeply should be the lead measure. It follows therefore that the individual scoreboard should be a physical artifact in the workspace that displayed the individual’s deep work hour count.”

Newport himself used the scorecard method by tracking his deep work hours on a notecard.

I like these “micro habits” and actually created a similar scorecard to what he describes in #3. I went so far as to design a downloadable template and create a website for it called weeklytracker.com but never fully developed that project. I guess it always came back to rule #1 where it didn’t make it to the top of the list of what was important.

Rule 2: Embrace Boredom

This one doesn’t sound very “productive” but to me a good way to think about this one is more along the lines of developing the skip of thinking deeply. Boredom may not be the best word to describe it, but he’s suggesting that many of us may be addicted to distraction, so the antidote is to learn how to quell those impulses to check things as soon as they pop into your head.

The practices he outlines in this section are, to me, perhaps the most important. Especially time boxing.

Essentially, you develop the habit of becoming more intentional with your time by assigning specific activities to blocks of time. Need to check email? Fine- just dedicate a particular amount of time to it. Need to work on an outline for a presentation? Work on that, but don’t swap over to your inbox during that time block. Simple to say but difficult to do. I think this quote from Newport sums it up best:

"Don’t take breaks from distraction... instead take breaks from focus."

Putting this into practice is one of the most challenging things and is actually what led me to create the Focus Timer. It’s specifically designed to support this portion of developing the ability to think deeply… and then putting that into practice (see rule 1)

But the ability to work deeply is like a muscle that must be developed. And working in these time blocks is the best way to train your mind. Even if you start with 5 minutes at a time, the routine will allow you to quickly expand the length of the sessions.

Rule 3: Quit Social Media

Ok, before you scroll past this one as a non-starter, what he’s really saying here is to be more conscious of the role social media plays in your life. And only incorporate it if it contributes positively to your goals.

He explains that in many cases, people have a visceral reaction to this recommendation and provide justifications. But the “any benefit” logic is faulty. Just because you can come up with one positive benefit doesn’t mean that on the whole it provides a positive contribution to your life.

Instead, he recommends taking a “craftsman’s approach to tool selection.” Every tool can accomplish a task but that’s not a justification for using a particular tool instead of a different one. Instead, one’s life goals should be considered in light of the role social media plays.

It’s kind of funny that he initially give an example of someone who went without social media for a month and says he’s not going to ask you to go that far… yet in his follow-up book Digital Minimalism, he really does essentially advocate that most people should not use social media. It goes to show the difficulty people faced in integrating Deep Work into their lives and how to him social media seems to be the culprit.

Rule 4: Drain the Shallows

In other words, don’t let shallow work get in the way of working deeply. He recommends that the best way to accomplish this is to schedule each minute of the day in blocks.

First, make a new list of the important things you need to do that day. Then predict the amount of time each thing is going to take. Using this, schedule the day’s blocks accordingly. This forces you to predict how much time each thing will take and be accountable for that estimation. Though I had already been practicing similar “time boxing” and the pomodoro method has delved deeply into this topic, the way Newport outlines it in the context of Deep Work is really powerful. If you’re familiar with the concept, his description will help you be more likely to put it into practice.

One objection he says he hears is that this practice will kill creativity due to the spontaneous nature of creative work. So Newport suggests that if a sufficiently interesting insight comes, he gives himself permission to continue with it and adjust his schedule. An interesting aspect he mentions is to schedule in “overflow blocks” as well to account for things like that.

I actually find that using time blocks helps with creativity even within the work session. Since my mind knows that there’s no need to check my calendar or email, it goes into creative mode more quickly and stays there. Then I can leverage the “overflow” method, knowing whether the next block is something that can be rearranged or not. (In fact, I just hit an overflow block in my time writing just now and decided to keep going.)

Building on Newport’s “craftsman approach to tool selection” I looked for years for a timer that could support my deep work how I wanted but wasn’t able to find one. I decided to make my own and if you think that might be helpful to you too, you can follow that project by signing up here.

I hope this article helps you understand the principles of Deep Work and incorporate them into your routines. I know I’ve benefited from them immensely.

0 Comments